The Levant’s golden era of cosmopolitanism

Paul Theroux’s journey around the Mediterranean basin in The Pillars of Hercules taught him that the coastal inhabitants of the Med had more in common with one another, no matter their nationality or faith, than they did with their brethren in the interior. By nature outward-looking, coastal cities are receptive to strangers, tolerant of difference and welcoming of strays in a way rare of inland cities. As such they have historically proven capable of nurturing a multi-faith, multi-ethnic cosmopolitanism. Three such cities are the subject of Philip Mansel’s Levant, which examines how cosmopolitanism took root in Beirut, Alexandria and Smyrna amid shifting loyalties born of Ottoman rule, foreign intervention and domestic dreams of independence.

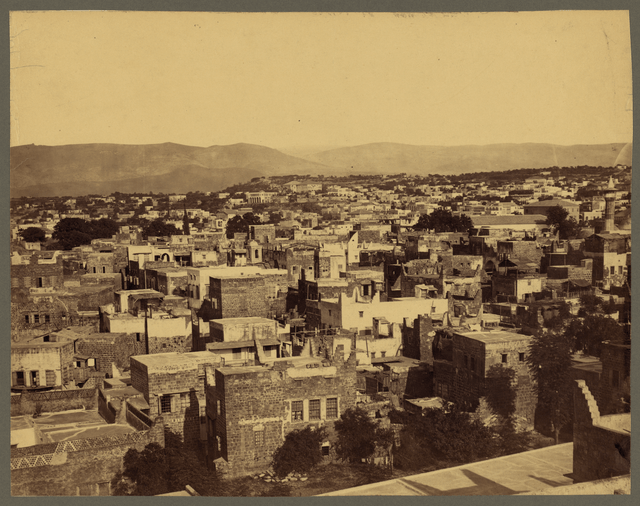

Each of Mansel’s cities come, or return, to prominence under Ottoman rule. Bolstered by the arrival of foreign traders, they develop in the nineteenth century into wealthy hubs of commerce. Such is their wealth or regional importance that they attain near-autonomy from Constantinople, with which each was, to a greater or lesser degree, discontented. Beirut, Alexandria and Smyrna also shared a rich ethnic and religious heritage, formed of different peoples with divided loyalties, at once to their native cities, to their faiths and to their ethnic groups. Supplanting these, however, was their first and most enduring loyalty, money. Beirut, where “unlike in Smyrna and Alexandria, the big money… was local,” was called home by Maronites, Alawis, Shia, Druze, Greek Catholics, Orthodox Christians and Jews. In a bid for advantage and eminence, each encouraged the patronage of the nations of Europe, who were more than happy to step in.

European diplomats, translators, merchants and consuls had formed part of the Levant for centuries and English, French, German, Dutch, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Greek and Austrian families were scattered across each of Mansel’s cities. They were drawn by the opportunity to make money, but were also enticed by the landscape of antiquity. Chateaubriand described Smyrna, by legend Homer’s birthplace, as “an oasis of civilisation.” In the Levant, Western settlers found – or thought they found – a freedom that couldn’t exist back home, and many that settled in the east stayed for centuries. Dutchman Edmond de Hochepied’s death in Smyrna in 1929, for instance, marked the end of his family’s 245-year presence in the city.

Europeans consolidated their influence in the Levant through the establishment of schools, charitable institutions, hospitals and churches. France was so successful in this regard in Beirut that it remains today tethered by historic bonds to Lebanon (Maronites, loyal to the pope, had sought France’s interference; the Maronites had even welcomed the Crusaders). Yet simmering beneath the apparent conviviality and bonhomie was a cocktail of suppression, jealousy and mistrust, as well as tensions – ethnic, racial, national and religious (racial tensions Mansel describes as “the hidden wiring of Ottoman history.”) The inability or reluctance of Constantinople to rule its subject cities with a firmer hand saw local chieftains assume control under the tutelage of European representatives. Western consuls were frequently more powerful than the Ottoman governors nominally in charge of local affairs.

One such ruler, Muhammed Ali, Pasha of Egypt from 1805 to 1848, emerges as one of the most interesting individuals in the book. Born in what is now Greece, and illiterate until his forties, he was a man of few illusions. Pragmatic and remarkably free of prejudice, Ali could also see that the pulse of the Ottoman Empire was flickering, and sought to carve out his own Egyptian empire from its still-breathing corpse. He recognised that the fatal Ottoman weakness was its failure to adequately respond to modernisation. Such modernisation was not just technological. In 1825, Ali permitted the ringing of Christian bells in Alexandria, dryly commenting that given there were so many religions, it would be a great misfortune if at least one were not true. This strikingly modern, ironic cast of mind was accompanied by a recognition that Alexandria could not rely upon God for protection; Alexandrians needed to put “all possible human effort into it.” It is Ali who sold many of the antiques that today line the rooms of the Louvre and British Museum.

Contrary to what one might expect, the European role in the Levant was not solely that of exploiter. Ottoman and French relations were robust, united first by their opposition to the Holy Roman Empire, and later by mutual admiration, with French the dominant language in Levantine ports (“Britain ruled the waves; France ruled hearts and minds”). Western presence also facilitated social progress. Smyrna boasted the first cinema, car, newspaper and racecourse in Ottoman lands. The incredible thing is that the Sublime Porte allowed Smyrna, Beirut and Alexandria such freedom; the truth is that it had little choice. Such was the number of Greeks, Europeans and Christians in Smyrna that Turks dubbed it Gâvur İzmir: infidel Izmir. But the concessions – or capitulations – granted by the Ottomans to foreigners grated on native Levantines. Moreover, inter-communal relations would occasionally flare up in violence. The collapse of the Ottoman Empire would release previously suppressed tendencies that, in the scramble for dominance, would lead to bloodshed.

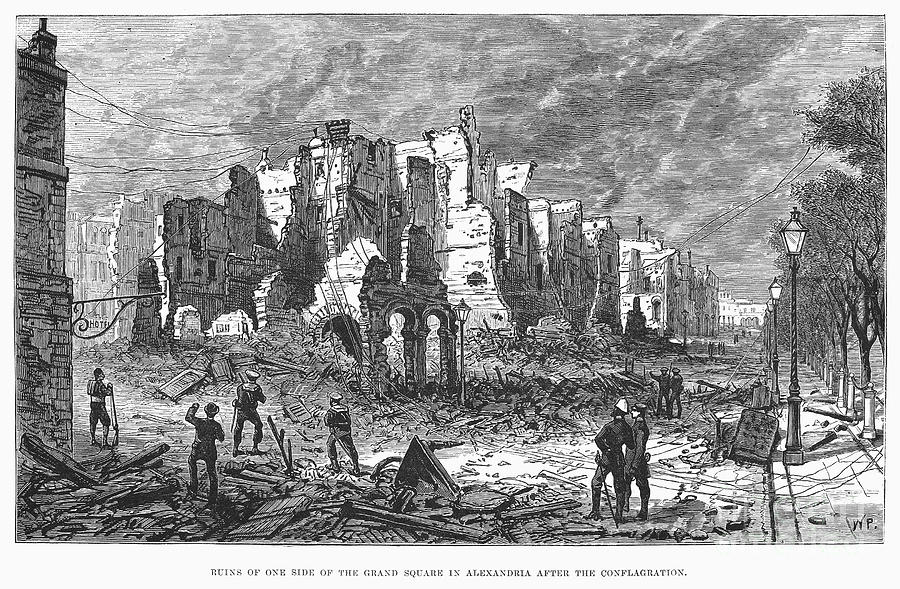

The seeds of the decline of these cities were already planted during their heydays. Amid all the soirées and salons in Alexandria, for example, Egyptians lived in desperate poverty and were treated little better than animals, by Europeans and by Turks, both of whom whipped Egyptians in public. Turks and Arabs, each equally contemptuous of Egyptians, loathed one another. European behaviour was often provocative and self-seeking, as in the British shelling of Alexandria in July 1882. This delights all Europeans – the British had rescued their cash cow. Meanwhile, Egyptian nationalism is given fresh impetus. Mansel demonstrates that contemporary anti-imperialist rhetoric is more than mere revisionism. General Sir Garnet Wolseley described the British bombardment of Alexandria as “silly and criminal” at the time.

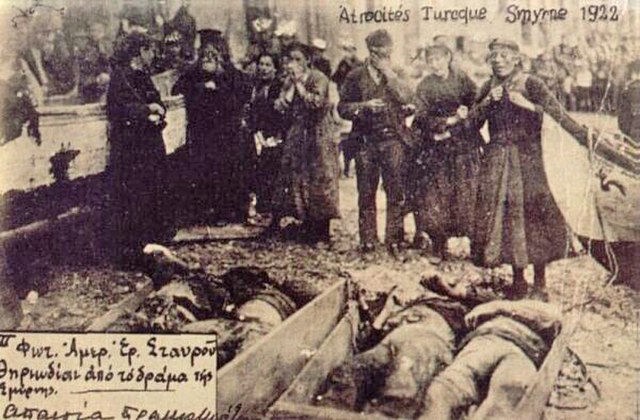

The rise of nationalism and religious fanaticism in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries fatally harmed relations between communities in each city. Greek nationalism in particular was the death knell for Smyrna. It also led to paradoxes. Greek massacres of Muslims and Jews in the Aegean and the Peloponnese in the nineteenth century saw some Greeks flock to wealthier, Ottoman-ruled Smyrna and Alexandria, thereby re-establishing – albeit unintentionally – Greek dominance in these ancient Greek cities. Their new superiority in numbers, combined with a groundswell of nationalist fervour across Europe, caused conflicts that would culminate in the catastrophic events of 1922. Greek troops, having devastated Anatolia, retreat to Smyrna. The Greek and Armenian quarters of Smyrna are then gutted by a fire starter by Muslims. A massacre of the Greeks ensues. Bishop Chrysostomos is lynched, his eyes pulled out. The city has never regained its former prestige.

Pluralism is crushed beneath a pitiless, oafish chauvinism. Ethnic and religious minorities are slaughtered or expelled, in Greece, in Turkey. Hellenization and Kemalisation prevails; cosmopolitanism is exchanged for a boring orthodoxy, in custom, in speech, in dress. Each city, Smyrna especially – renamed Izmir – slides into torpidity. The opening decades of the twentieth century, as Mansel notes, also sees port cities robbed of their importance. Superiority on the waves, and proximity to the ocean, declines in importance as technology evolves; St Petersburg is relegated beneath Moscow; Constantinople gives way to inland Ankara. Diverse Trieste, Odessa and Izmir are homogenised. Beirut and Alexandria retain their cosmopolitanism for a while longer before they too are beset by conflict or monolithic rigidity. Those families that had helped make Beirut, Alexandria and Smyrna prosperous pack their bags, never to return.

Levity comes in the form of Mansel’s primary sources. One visitor to Smyrna extolled the virtues of the wine on offer, which was “so exquisite that unless you are naturally doltish, you have to lose there all the malignity of melancholy.” Another, Englishman Norman Douglas, wrote in 1895 of Smyrna’s “Greek quarter full of pretty girls, far prettier than those of Greece itself… The fortnight in Smyrna… proved to be one of the happiest of my life.” I’m sure it did, Norm. The Portuguese novelist Eça de Queiroz, writing of Alexandria, despaired at the profusion of Englishmen and their conduct: “The world is becoming Anglicized. The English are everywhere, that is why they are detested, they never integrate or de-Anglicize themselves.”

Mansel’s book would surely mark as a failure if it didn’t inspire fantasies of going back in time and visiting the cities under discussion. By this measure, but not by this alone (Mansel is a wonderful writer), it is a success: one wants to stroll down the Frank road in Smyrna, to look out over Alexandria’s harbour from the Ras el-Tin or to drink and sing in Beiruti gardens. It’s considered rather gauche, post-Edward Said, to look on the Levant as an exotic Other – but when it is exotic, what else can one do? The very language is irresistible: pasha, dragoman, janissary, vizier, khedive… The louche atmosphere of these cities, in particular Smyrna, makes them places one wishes one could have seen at their height (but only if one had plenty of cash).

Beirut, Alexandria and Smyrna each sustain long periods of cosmopolitanism to which only the dullest mind could object. The problem is that they were held together only by money or the protection of foreign armies. Even at these cities’ zeniths, persecution was common; intermarriage, a marker of true cosmopolitanism, was rare. Riots in Smyrna in 1821, in Beirut in 1860 and in Alexandira in 1881 foreshadowed even greater violence to come, and were in effect fissures that revealed these cities’ underlying instability. Mansel argues that the spirit of the Levant now resides in megacities like Mumbai, New York and London, where people from all over the world co-exist with greater ease than they do today in the Middle East. Perhaps different people can live together more or less in peace – but only if the going is good.