“It was over a question of honour, people say”

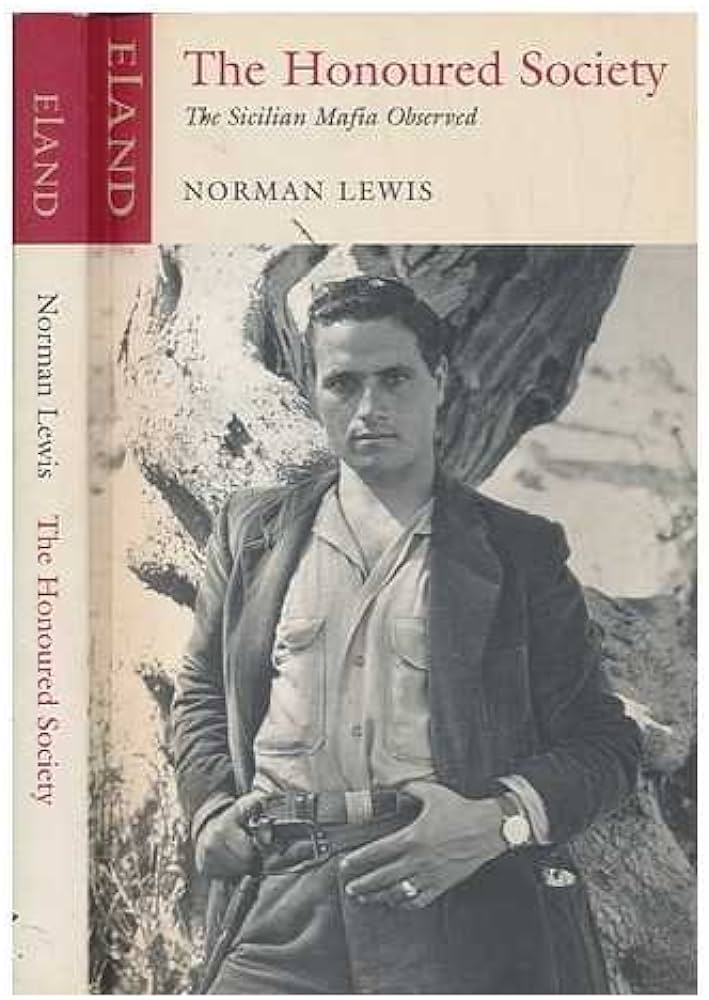

The Sicilian Mafia is so deeply rooted in the popular consciousness that it is difficult to remember that its very existence was once open to doubt. The Honoured Society played a big part in bringing Cosa Nostra and its arcane rites and esoteric codes to the English-speaking world’s attention. It deals with the period when the Mafia’s rumoured influence was only just beginning to be established as concrete fact – before the drug trafficking and blood-letting of the ’70s, before the Mafia-run construction boom that ruined Palermo, and before the Maxi trial of the late ’80s, and the assassinations of Borsellino and Falcone.

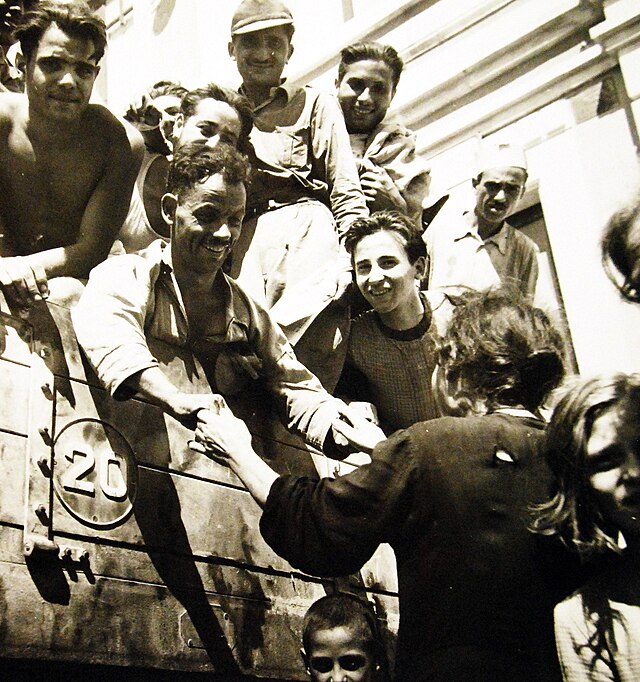

This is the story of the Mafia’s efflorescence in post-war Sicily, and the roles played by the aristocracy, by the police and by political parties in helping this come about. The centrifugal figure from which Mafia power emanated, and the person whose shadow stalks every sentence in the book, is Calogero Vizzini, better remembered as Don Calò, the tight-lipped mayor of Villalba, “boss of bosses” and emblem of our stereotypical notion of the Mafia don. His unassuming appearance belied a ruthless thirst for power. It was to Don Calò that American troops turned for assistance during the invasion of Sicily, and such was his reputation that they were able to sweep across the west of the island with hardly a shot fired.

The tale that Lewis relates is almost comically surreal, yet what stands out amid the incredible revelations is Lewis’ potent evocation of an island suffocated into submission and silence. Woven into the narrative are vivid impressions of Sicilian life and a potted history of the island that provides the context for how the Mafia was able to consolidate control over a people living in a “state of massed hypnosis.” Lewis, whose first wife was Sicilian, interrogated local sources, but also relied on the testimony of those Sicilians bold enough to put their heads above the parapet, most conspicuously Danilo Dolci, whose Waste (1960) laid bare evidence of the Mafia’s corrosive influence.

Lewis touches on the Mafia’s 19th century roots, but the story really begins in the fascist period. Mussolini had sought to the crush the Mafia, correctly identifying it as a threat to his one-man rule. On a visit to the Sicilian town of Piana dei Greci in 1924, the arrogance of the local Mafia don Francesco Cuccia kindled Mussolini’s wrath. To bring him and his honoured associates to their knees, Il Duce leaned on his time-worn tactic of violence, engaging the services of Cesare Mori, a police officer known as Il prefetto di ferro (“the iron prefect”) due to his reputation for getting the job done, usually via the application of torture.

Mori’s savagery worked and mafiosi influence waned. The problem was that the Mafia hadn’t gone anywhere. Mori had subdued, but not destroyed, organised crime. In the wake of the fascist state’s assault upon their activities, Sicilian mafiosi either fled to the United States or acquiesced to the authorities’ demands and waited patiently. Mori’s anti-Mafia campaign had merely “scythed the heads off a crop of weeds when what was needed was a change in the soil and climate that produced the crop.” It is thus no surprise that the Mafia was more than willing to help the Allies liberate Sicily from fascism, but it was in the cause of their own interests, not Sicily’s, that they did so.

So determined was the Mafia to re-establish its grip on the reins of power that, amid the collapsing scenery of the fascist government’s fall, it sought to separate Sicily from Italy to become a member of the United States. The Americans, aware that the Communist Party of Italy was enormously popular and would garner a lot of votes in the restored democratic Italian parliament, cynically encouraged Sicilian separatism. When the Americans saw that the idea was losing momentum – and that it would actually be the Christian Democrats most likely to return the highest number of delegates – Sicilian separatism was quickly dropped. The Mafia, hyper-alert to changes in the political wind, followed the American’s lead. Don Calò – thanks to the interference of the Carabiniere chief General Branca – went unpunished for his part in the separatist scheme. “Everything possible was to be done to restore normality in Sicily” – including the mafiosi retaining the last word in Sicilian politics.

For this to happen the Mafia had to quell a number of threats. Some of them were familiar, like the landowners, but others were novel. Trade unionism was among the most important. The perennial peasant demand for better wages, conditions and land finally seemed a real possibility in the leftist momentum sweeping through post-war Italy. In Sicily, attempts were made by the peasantry to establish co-operatives on uncultivated land, which the Mafia successfully thwarted by ensuring it remained in the hands of the aristocracy or seized it for themselves. The Mafia would go on to supplant the aristocracy to become the benevolent, paternalistic landowners of naive legend.

Lewis traces the vested interests and political ideologies that clashed in a bid for supremacy in the new democracy. In Sicily, the struggle saw the Christian Democrats – backed by local landowners and the church – go up against a progressive coalition formed of communists and socialists. Enormous pressure was put on Sicilians to vote for the Christian Democrats, backed as they were by the Mafia (one mafioso: “Vote for the Communists, and we’ll leave you without a father or mother”). And on the Italian mainland, the Christian Democrats did indeed emerge victorious. But somehow, to everyone’s stunned astonishment, Sicilians opted for the candidates of the left.

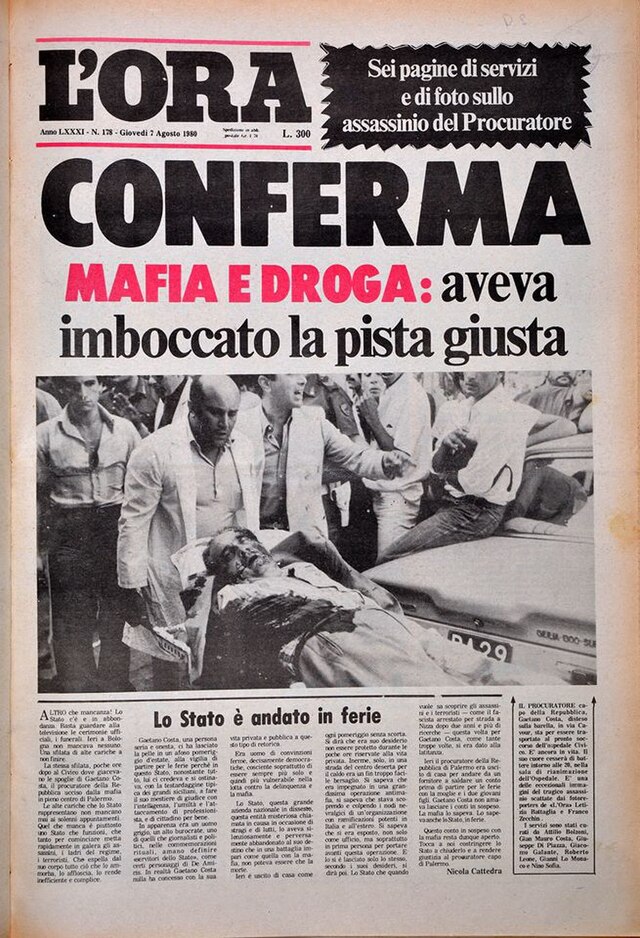

This was a slap in the face to more than a few interested parties, each of whom believed it could control the peasantry according to their own ends: the church, the baronial landowners and, crucially, the Mafia. It was not to go unpunished. On 1 May 1947 Sicilian peasants gathering at Portella della Ginestra for an annual festival of speeches, dancing and feasting were fired upon from the mountains. Men, women and children were sprayed with bullets at random. Eleven were murdered and many more wounded. The man behind the slaughter was Salvatore Giuliano.

Giuliano was the most notorious bandit in Sicily. Handsome and enigmatic, he cultivated the image of himself as a modern Robin Hood, and achieved widespread popular support for his sticking it to the barons. He was tolerated by the mafiosi, who sometimes drew on his services, so long as he steered clear of the towns where their rule was entrenched. Giuliano and his band had been key players in the aborted bid for Sicilian separatism. But now, with the Mafia back in the saddle after the dismal years of fascist oppression, and with the heady days of separatism over, it was becoming increasingly unclear for whom Giuliano was working. The question was who had ordered Giuliano and his desperadoes to kill the peasants.

Giuliano, protected by the Mafia in Castelvetrano, was captured and slain in confusing circumstances in January 1950. On trial in Viterbo for the Protella murders was Giuliano’s cousin and and second-in-command Gaspare Piscotta. Prosecutors were curiously reluctant to hear his testimony. The reason why was soon revealed.

We were a single body… bandits, police and Mafia, like the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost.

Pisciotta also informed the court that he had shot and killed Giuliano:

I realised that the Christian Democrats had fixed up everything for Giuliano to get away, and leave us to face the music. So I killed him.

Supplementing this verbal evidence was a tranche of letters and valuable permits addressed and issued to Pisciotta from the police. Worse, Pisciotta told the court that not only had he been to Rome to meet the Minister of the Interior Mario Scelba (later to become Prime Minister of Italy) but that the most senior culprits for the Portella killings had fled the country with the connivance of the government. Transferred to a Palermo prison to stand trial for the murder of Giuliano, Pisciotta was poisoned in his cell. Nobody was charged.

Lewis draws upon his superb command of English to conjure, with very few words, rich sketches of character and place, such as the town of Corleone, now indelibly linked to Cosa Nostra thanks to Mario Puzo, which

… is built under a lugubrious backdrop of mountains the colour of lead, and its seedy houses are wound round a strange black rocky outcrop jutting up from the middle of the town. Upon this pigmy mesa is built the town lockup, and from its summit the crows launch themselves in search of urban carrion.

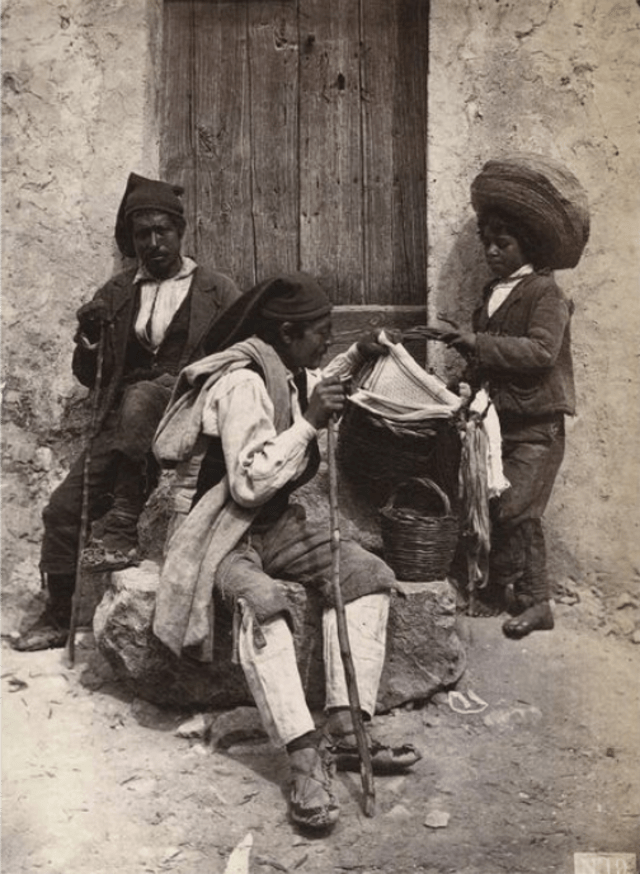

Such is the spirit of Sicily evoked, an island whose inhabitants, Lewis reminds us, have been subjugated since time immemorial. In his telling, time in Sicily has been flattened – the past is also now, and forever, a perspective memorably captured in the character Tancredi in Lampedusa’s The Leopard, who reflects that “If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.” The town of Montelepre and the surrounding plain, where “the voracious colonisation of antiquity consumed slaves by the thousand,” “reek” of the past. It is Lewis’ facility with language the keeps one on track among the incestuous complexities of Sicilian political and criminal life.

The 1950s would see a new wave of gaudy mafiosi who, inspired by the conspicuous wealth of their fellow gangsters in Chicago and New York, departed from the rustic simplicity of their forebears. There avarice would accelerate the bloodshed that would reach its apogee in the frenzied murders of the 1970s. But what of Don Calò, that illiterate every-man who had manipulated all around him during the dizzy days of allied liberation, thwarted separatism, political machinations and roving banditry? He died aged 76 of a heart attack. His final words – “how beautiful life is!”