“Naples is extraordinary in every way”

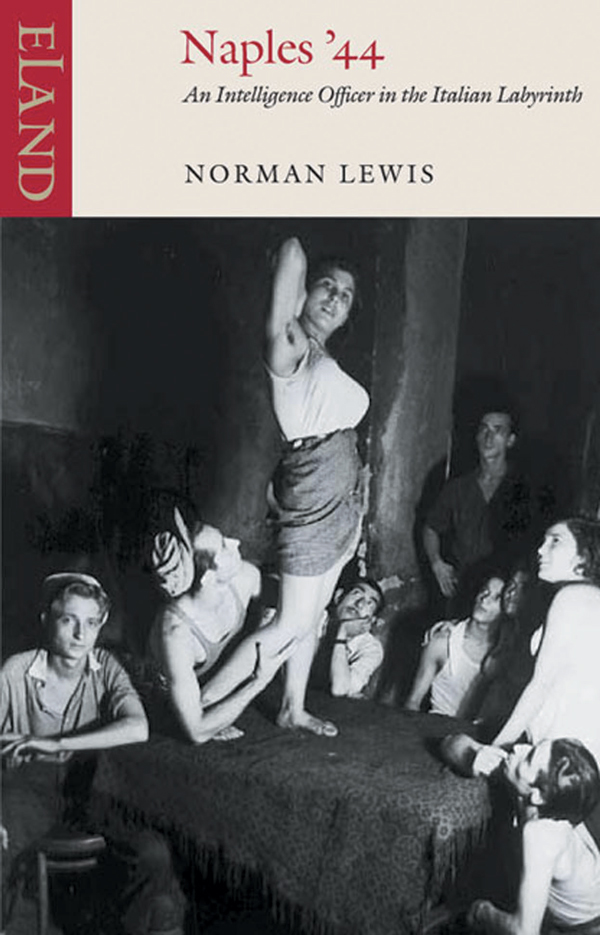

Naples ’44, the diary of Norman Lewis, a British intelligence officer posted in Naples during the Allied occupation, has correctly been hailed as his masterpiece. Lewis’ entries, from September 1943 to October 1944, are an invaluable and devastatingly absorbing account of a people crushed by violence, disease and privation. They are also laugh-out-loud funny. Sympathetic and unwaveringly honest, Lewis writes in an exquisitely taut prose that is, as Orwell advised all good prose should be, “transparent, like a window pane.” Permeating Lewis’ narrative is his integrity, often his frustration and disgust, but always his admiration for Italians and southern Italy. Occasionally, one stumbles upon a book that is like a slap in the face. Naples ’44 is such a book.

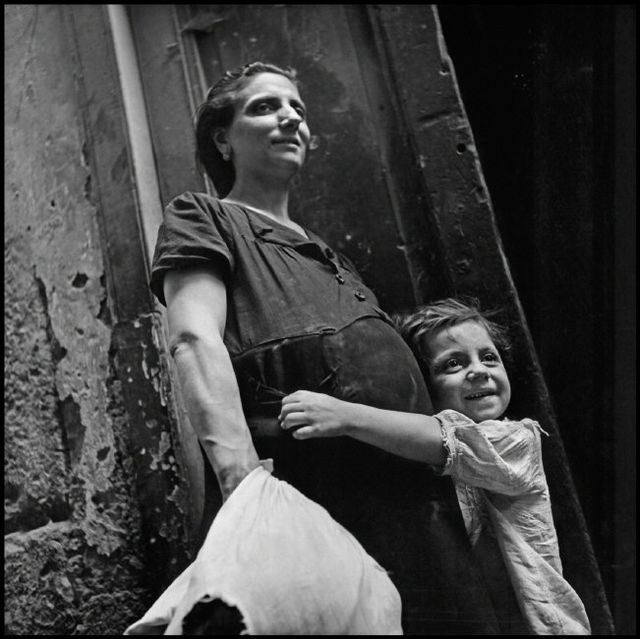

Brigands, child prostitutes, destitute noblewomen, half-feral children; volcanic eruptions, murder, rape and castration; bombing raids, starvation, delayed-action explosives; love affairs, denunciations, brutal violence; the Camorra, honour killings, omertà; endless theft, poverty, exhaustion, hunger. This is the Second World War in real time as lived by its participants, raw and unglamorous. No glory finds its way into Lewis’ record, nor any trumpeting of the broader war aims or moral rectitude. He writes of the Allied command’s disorganisation and ineptitude with a clarity that, while damning, is without rancour. But what the book is really about is Lewis’ colourful impression of Neapolitans and their extraordinary city, and how they toil and suffer – and sometimes thrive – amid the collapse of ordinary life.

The book opens with Lewis aboard the Duchess of Bedford bound for Paestum, near Salerno, on 9 September 1943, days after an armistice is agreed between the Allies and the Italian government, and following successful Allied landings in Calabria. Having sailed from Algeria, where he had been deployed as a sergeant in the Intelligence Corps, Lewis is attached to the HQ of the US Fifth Army, his role to liaise between locals and Allied troops, establish contacts, monitor and report on counter-intelligence and help maintain law and order. In truth, his responsibilities are “vague” and the main impression Lewis gives is one of trying to make the best of a hopeless situation.

Nearly every page has an arresting anecdote. Approaching Naples from the south, Lewis happens upon a mob of Allied soldiers descending on a derelict building. Inside, having pushed his way to the front of the baying crowd, he finds a row of local women, seated at intervals before a wall:

By the side of each woman stood a small pile of tins, and it soon became clear that it was possible to make love to any one of them in this very public place by adding another tin to the pile. The women kept absolutely still, they said nothing, and their faces were as empty of expression as graven images.

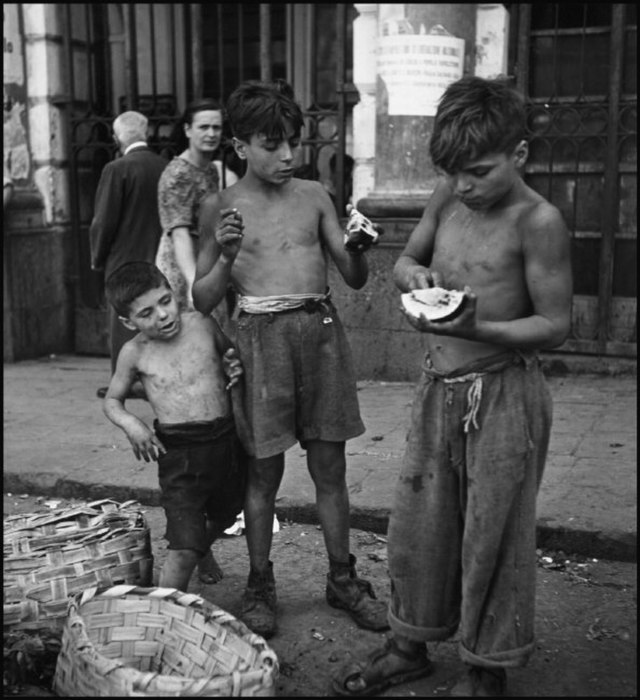

This early passage is typical Lewis and indicative of what is to come: a sordid or bizarre scene, evoked with concision and a perceptive eye. One of the most vivid episodes in the book is Lewis’ visit to restaurant with a Neapolitan contact, Lattarullo, “a man steeped in the knowledge of the ways of Naples,” and a “professional mourner” – that is, someone paid to turn up at Neapolitan funerals in the guise of a distinguished “uncle from Rome” of the deceased, the intention being to confer class on the proceedings for the family of the departed and to impress onlookers. As Lewis and Lattarullo dine, a posse of ragged boys clamber in from the street to beg for scraps of food:

Once again, I couldn’t help noticing the intelligence – almost the intellectuality – of their expressions. No attempt was made to chase them away. They were simply treated as non-existent. The customers had withdrawn from the world while they communed with their food.

A disabled boy, wheeled in on a makeshift skateboard face-down, and hand-fed leftovers by the boys, soon follows, before a group of weeping little girls appear in the doorway, each of them from an orphanage for the blind. “Tragedy and despair had been thrust upon us, and would not be shut out.” Every customer, however, goes on eating. This distressing event Lewis marks as a departure from his former view of humanity: “Until now I had clung to the comforting belief that human beings eventually come to terms with pain and sorrow.” Now Lewis recognises that some suffering is unassailable: “I knew that, condemned to everlasting darkness, hunger and loss, they would weep on incessantly. They would never recover from their pain, and I would never recover from the memory of it.”

His daily responsibilities lurch between the tedious and the alarming, the former mainly concerned with the “flood” of denunciations Neapolitans bring to Lewis’ door. These are ostensibly concerned with reports of theft, or the suspicion that a neighbour is a spy or saboteur, but are overwhelmingly the result of petty feuds and jealousies. More serious is organised crime, and the continual pilfering of Allied goods sold openly on the street. Lewis nevertheless forges strong relationships with the Neapolitans, and though invariably baffled by their carrying on, he is impressed by their humour and resolve. What he sees is often incredible,but Lewis is never lurid or aloof to what they are enduring. He also learns to understand what it is to be Neapolitan (“Again the vendetta”) in a city pummelled by loss and deprivation.

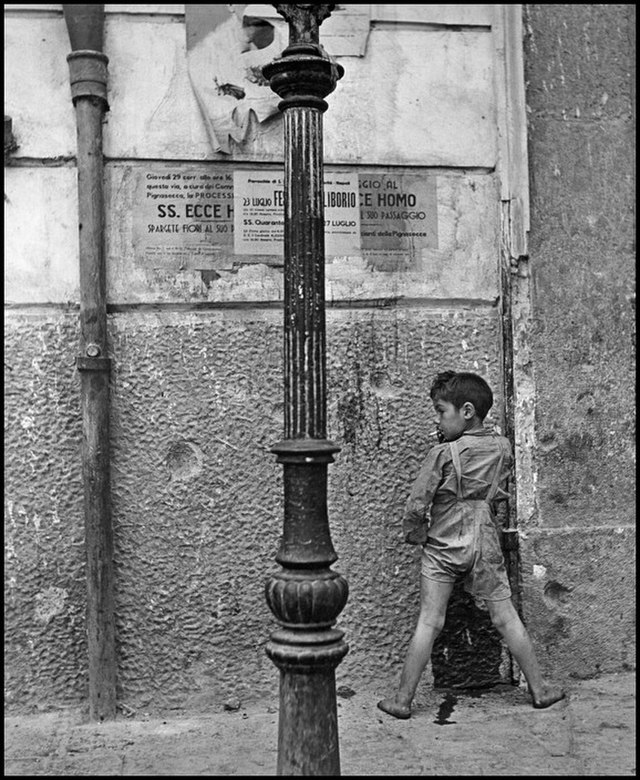

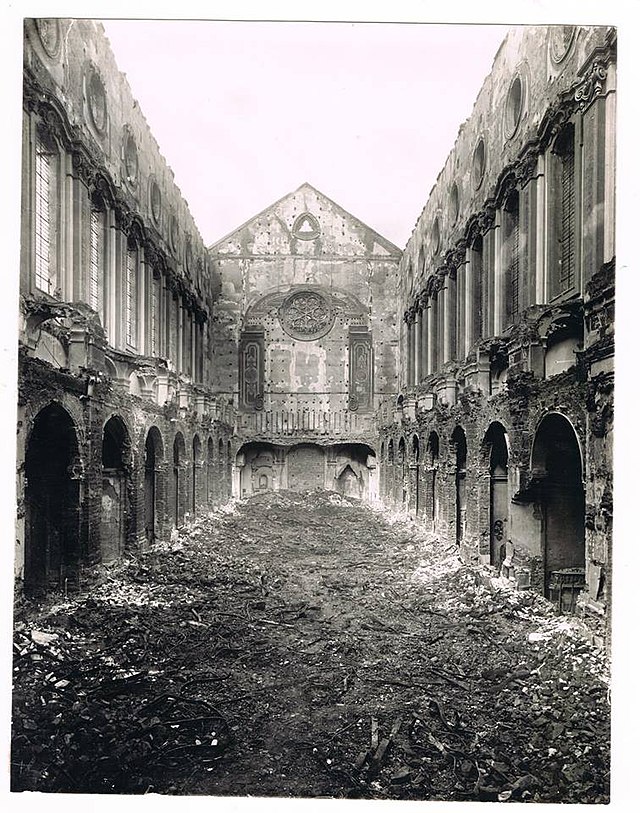

What is extraordinary is that normal life of any kind could continue in the city, which had already endured Nazi rule and Allied bombing. Delay-action explosives, planted by the retreating Germans, combined with regular Nazi bombing raids on the port, kill indiscriminately and cause terror and devastation. Rubble litters the streets, and food is so scarce that Lewis witnesses Neapolitans venturing into the country in search of dandelions, or prying limpets off rocks in the bay, for sustenance. Money is so desperately sought that some parents prostitute their children. A flourishing trade in adult prostitution sees venereal disease surge, while typhoid and, in the country, malaria (which Lewis contracts three times) proliferate. Penicillin becomes a precious black market commodity. The inevitable result is a rise in superstition: “Everywhere there is a craving for miracles and cures. The war has pushed Neapolitans back into the Middle Ages.”

Hastening the wave of credulity engulfing Naples is the eruption of Vesuvius, with colossal ill-timing, on 19 March 1944:

At night the lava streams began to trickle down the mountain’s slopes. By day the spectacle was calm but now the eruption showed a terrible vivacity. Fiery symbols were scrawled across the water of the bay, and periodically the crater discharged mines of serpents into a sky which was the deepest of blood reds and pulsating everywhere with lightning reflections.

Lewis is sent to the town of San Sebastiano, on Vesuvius’ western slopes, to assess the damage. On arrival he finds lava creeping down the town’s main street, picking up and devouring everything in its path, entire buildings included. San Sebastiano’s residents are arranged together only yards away, kneeling in prayer and armed with banners depicting religious images. “Occasionally a grief-crazed citizen would grab one of the banners and dash towards the wall of lava, shaking it angrily as if to warn off the malignant spirits of the eruption.” Others hold up icons of the town’s namesake in an appeal for holy intervention. Lewis notes, however, a rival: a statue of San Gennaro. As San Gennaro is the patron saint of nearby Naples, there is concern that this statue’s presence in the town might suggest a lack of local faith in San Sebastiano’s powers of protection, and thus give cause for divine offence. With typical ingenuity, the residents of San Sebastiano keep the San Gennaro statue in reserve in a side-street just in case, and cover it in a white sheet.

Already enduring immense material want, a natural disaster is the last thing Neapolitans needed. And yet, as Lewis shows, they find a way to survive. Anyone who has been among Neapolitans will recognise there depiction in Lewis’ book. Resigned to their fate, still they are warm and hospitable, relying on their limitless aptitude for adaptability and resourcefulness to get by. Expecting nothing, they are never disappointed, and muddle on with unassuming persistence, though Lewis is often exasperated by their stubborn superstitions and unshakeable predilection for charms and lucky symbols. The Neapolitan love of the occult crops up time and again, including in Benevento where, encountering a coterie of local men suspicious of his intentions, he notices “a sly movement of every left hand towards the right side of the crutch” to ward off the evil eye brought about by Lewis’ presence (dryly, he adds that this is “A disconcerting confirmation of loss of favour”).

The suburbs and the towns strewn beyond the city proper, which Lewis visits as part of his duties, are bleak to the point of despair, and are not spared the accompanying effects of war. Again in Benevento, Lewis records seeing an old man prone in the street, dying, as people pass by. Those settlements not totally dominated by the Camorra are seething hotbeds of brigandage. Local Carabinieri, ill-equipped, isolated and outnumbered, are almost totally powerless and live in a state of continual siege. These condemned outposts draw from Lewis a mixture of pity and revulsion, and it is here that he meets that unfailing method of survival that every local must wield in order to continue living: omertà. The “conspiratorial silence of the South” Lewis recognises following a ritual killing, where the local population had been “bred to silence. They were drugged with caution.” Vito Genovese, working hand in glove with the Americans, makes two disparaging appearances in the diary, helping set up Camorristi mayors in the towns that cluster north of Naples.

One of the principle ways Neapolitans alleviate their hardship is also one of the great motifs of Lewis’ diary, sex. “The sexual attitudes of Neapolitans never fail to produce new surprises”, writes Lewis in an entry on a Neapolitan cemetery where couples gather to copulate away from prying eyes in the city. One of Lewis’ Italian informants, Lola, seeks Lewis’ services as translator between herself and her English lover, Captain Frazer, the latter of whom confides in Lewis one of Lola’s unsettling tics:

She also had a habit, which terrified Frazer, of keeping an eye on the bedside clock while he performed. I recommended him to drink – as the locals did – marsala with yolks of eggs stirred into it, and to wear a medal of San Rocco, patron of coitus reservatus, which could be had in any religious-supplies shop.

War and living in the shadow of death give an extra erotic charge to the already priapic Neapolitans, but it also leads to another, uglier current that pulses through Southern Italian veins: vengeance. One entry sees Lewis assisting Carabinieri in the ambush of a notorious brigand called Lupo, who has been betrayed to the police by his mistress. As he is cuffed and led away, Lewis protests to an officer present that the mistress is being treated somewhat brusquely by his officers.

‘They’re rather rough with her, aren’t they?’ I said.

‘She’s let her man down. They don’t like that kind of thing.‘

‘But she’s been working for you.‘

‘It doesn’t mean we have to like her.’

‘What will happen to them now?’

‘He’ll go down for life, and one of his brothers will kill her. They’ll soon find out she threw him in. A knife up through the vagina into the belly. Or a red-hot poker if they have time. She’ll be dead within the year.’

Lewis is not always faced with horrific violence of this kind, but when he is, it’s hard to forget. Another entry, from the summer of 1944, tells of the live castration and decapitation of French soldiers of north African descent who had been raping local women. Lewis navigates this hyper-violence with characteristic stoicism and ironic humour. Confronting a convoy of armed brigands, he resolves, “with a drowsy determination to avoid killing or getting killed.”

Lewis is superb at distilling the spirit of a place in only a few words. From the height of the Vomero, he describes how Naples is “spread out beneath us like an antique map”, a view which he later notes presents a “totally fallacious aspect of dignified calm.” His diary is also sprinkled with evocative vignettes that lend vivacity to his account and bring Naples to life. A passing broom seller trundling by Lewis’ window has “a cry like a muezzin calling the faithful to prayer.” Some entries are little jewels of detail and pathos, such as that of 15 March 1944:

A bad raid last night with heavy civilian casualties, as usual, in the heavily populated port areas. I was sent this morning to investigate the reports of panic, and frantic crowds running through the streets crying, ‘Give us peace!’ and ‘Out with all the soldiers.’ In Santa Lucia, home of the Neapolitan ballad, I saw a heart-rending scene. A number of tiny children had been dug out of the ruins of a bombed building and lay side by side in the street. Where presentable, their faces were uncovered, and in some cases brand-new dolls had been thrust into their arms to accompany them to the other world.

The diary is riven with references to Naples and its environs having descended to a quality of life akin to the Middle Ages, even the Bronze Age, and amid the deleterious conditions, Lewis recognises that though they had helped rid Naples of the Nazis, the Allied troops were no longer welcome either (“these people must be thoroughly sick and tired of us.”). Nascent attempts to resurrect the democratic process has Lewis at his most pessimistic: “The glorious prospect of being able one day to choose their rulers from a list of powerful men, most of whose corruptions are generally known and accepted with weary resignation. The days of Benito Mussolini must seem like a lost paradise compared with this.”

Such cynicism is atypical. More usual is Lewis’ amazement at what he sees around him, not only the effect of war, but everyday Neapolitan life:

Last week a nobleman in our street was lifted by his servants from his deathbed, dressed in his evening clothes, then carried to be propped up at the head of the staircase over the courtyard of his palazzo. Here with a bouquet of roses thrust into his arms he stood for a moment to take leave of his friends and neighbours gathered in the courtyard below, before being carried back to receive the last rites. Where else but in Naples could a sense of occasion be carried to such lengths?

Towards the end of 1944, after over a year in Italy, Lewis is suddenly ordered to leave (“The thunderbolt has struck”) for Port Said. The book ends with Lewis reluctantly packing his bags, rueful that he has no time to say his goodbyes. Naples ’44 is an invaluable account of one man’s wartime service, but it is also the story of how a man falls in love with a people and their city, Naples – a place “that had ignored and finally overcome all its conquerors, dedicated entirely and everlastingly to the sweet things of life.”