Resilience and resurrection in Central Europe

November 2023

If geography is destiny, then Poland has been ill-fated in having been handed some truly formidable neighbours. The Soviet Union, Third Reich, Russian Empire, Prussia – the aphorism that it was not a state with an army, but an army with a state, is itself instructive (attrib. Mirabaeu) – and the Austro-Hungarian Empire have each come and gone next to Polish borders, usually crossing over them. That was then. But even today, threats are near at hand. Blood is being spilt next door in Ukraine, and the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad is nestled petulantly on Poland’s north-eastern flank, home to Russia’s Baltic Fleet.

Heady and serious stuff, yet so goes Polish history. The footfall of Cossacks, the Red Army, Teutonic Knights, Napoleon’s Grande Armée and Einsatzgruppen death squads have all marched over Polish soil. The richness and changing nature of its history is born out in place names – Gdańsk, formerly the Free City of Danzig, and Breslau, now Wrocław – as well as shifting borders, with Lviv, now in western Ukraine, formerly Lwów as part of the Kingdom of Poland or, in German, Lemberg. Polish nomenclature is inescapably resonant with history: Silesia, the Pale of Settlement, Galicia – and Treblinka and Auschwitz-Birkenau.

All of which makes visiting Poland for the first time ever-so-slightly daunting, but for lovers of history, irresistible. I was not disappointed. In Warsaw for a few days, I was exposed to a panorama of conflict, defeat and resurrection: here, the monument to the Warsaw Uprising and the Solidarity movement, there the sprawling Soviet Cemetery and the remains of the wall of the Ghetto. That anything is left of Warsaw to see is testament to the endurance of the Polish people, Himmler having ordered that it must “completely disappear from the surface of the earth” following the defeat of the AK (Home Army) in the Uprising of ’44, the largest resistance to Nazi rule in Europe.

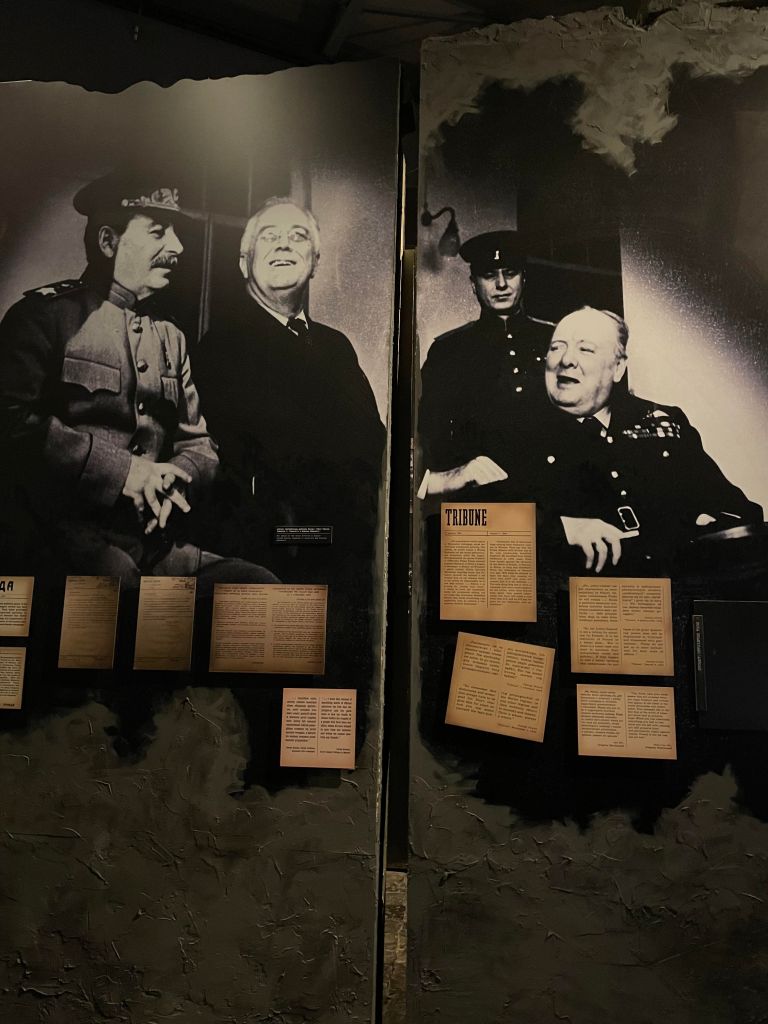

The Old Town, a warren of pretty cobblestone streets and squares, was meticulously reconstructed post-war. The Nazi withdrawal and defeat, in a just world, should have heralded better days. But having suffered the degradations of one neighbour, another immediately came marching across the Vistula. For the next 45 years, Poland was held against its will within the Soviet sphere of influence. The sheer unfairness is hard to comprehend. AK members who had bravely resisted the Nazis were arrested. In 1945, sixteen members of the Polish Underground were kidnapped by the NKVD, taken to Moscow, interned and tortured. Among the charges was “collaboration with Nazi Germany”. Their trial wasn’t clandestine or hushed up, it was explicit, brazen, open. Twelve of them received prison sentences; three died in Soviet captivity. It was difficult to read of my own country’s complicity and silence in such scandals to keep our Soviet allies happy.

The POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, housed in a steel and glass edifice with an awesome, cave-like interior, takes one on a tour of 1,000 years of Jewish life in Poland, with model shtetl, wooden synagogues, classrooms and other locales of daily life. Here the tension between assimilation and tradition is probed, as well as the waxing and waning of relations between Jews and Poles. Thus we veer from hostility and oppression to concord and collaboration. The diversity of Jewish thought is given full expression, from interwar socialists to religious conservatives. The permanent exhibition reaches its denouement with the Nazi invasion, the Ghetto and the camps. The written and material evidence is soberly displayed in precise yet lucid detail, but it is the personal testimony – diaries, letters and photographs – that is most penetrating. Not easily forgotten.

If one needs to take the edge off after that, then one can, as I did, fortify oneself with a few cans of Tyskie. But it would be misleading to think of a visit to Warsaw as a humourless sojourn through tragic tableaux. At the Museum of Life under Communism, the tone is comical. Its website promises to take you “back in time to experience everyday realities and absurdities of the 1944-1989 communist era in Poland”. True, portraits of Brezhnev – he of the indomitable brow – and Lenin greet one on entry. But the emphasis was very much on the homely and the familiar, even the nostalgic. There was a mock-up of a flat from the 70s that was supposed to reflect the sparse and rather bleak reality of communist life. As I stood in it, reflecting patronisingly on those poor Poles who had to live under the communist cudgel, I realised – with appalling clarity – that it was larger, better stocked and more lavishly decorated than my own poky abode in 2023. Much Tyskie was consumed that night brooding over that recognition.

Outside on Constitution Square, narrow trams with red and yellow livery glide elegantly between the heavy traffic. Here, the streetscape is socialist realist, part of Warsaw’s many and varied architectural styles. At the city’s heart a few miles up the road looms a Stalinist relic in the Palace of Culture and Science, an enormous postwar clocktower tower modelled on Moscow’s Seven Sisters. Today, it is framed by ultramodern skyscrapers, but the square beneath the palace is so vast that it still looks isolated and lost, like it has landed from another planet. Built at the behest of Stalin, it kind of was. Vestigial reminders of an older Poland were more welcoming. The first I saw of the city on approach was the majestic towers of St Florian’s, a Gothic Revival redbrick destroyed during the war and rebuilt, lit up from across the Vistula.

On a quest for further “positive vibes” I took in a recital at the city’s archdiocese of the work of Warsaw’s most famous resident, Chopin. In the service of a scrupulous fidelity to truth, I here must confess that, during a particularly hypnotic number during the first half, I fell asleep. That’s no comment on the brilliant pianist (he was really going at it when I slipped away) or indeed on Chopin. My public dozes are exquisitely fair and balanced: I’ve nodded off at the cinema whilst enduring Fast and Furious 8 (better known to F&F purists as The Fate of the Furious) and at the theatre during Rigoletto. Sat slumped in my chair chin‐to‐chest, I can only apologise to the shade of Chopin. I was tired.

Warsaw’s emblem is a mermaid brandishing a shield and sword. At the heart of the Old Town is a much-photographed figurative representation. Beautiful and tough, and more defensive than belligerent, I can’t think of a better symbol for the city. Warsaw works hard to convince itself and others that solidarity and perseverance mean that the bad cannot triumph over the good for long. We had better hope that this is true.