June 2023

We sat in the waiting room at the police station.

It had the look and feel of a hospital. The room was small and brightly lit and sparsely furnished: a row of four blue plastic seats, a vending machine and a small coffee table. The walls were bare save for one, directly opposite us, which featured a display. It was a shrine. At the top hung a wooden crucifix. Beneath it, two portrait photographs of police officers in uniform, both male, with accompanying biographies. These explained how and when they had been murdered. Underneath their photographs was a dedication to the officers, and a vow to remember those in law enforcement lost to the mafia’s hand. Propping it up was a framed prayer to Saint Anthony of Padua. It was all exquisitely arranged, to the inch. Someone had taken great care to ensure it looked right.

While we waited, officers milled about and chatted in the hall, sometimes wandering in to jab at the vending machine. Every ten minutes or so, a new face would poke their head around the door and speak to Annalisa, who after lunch had proposed we go and collect a copy of her driving licence. I never got to the bottom of whether she had lost her previous one or whether it had been confiscated. The officers were in that very smart summer garb of rich navy shirt, greyish trousers and black boots. Each had a gun securely fixed to their belt. They were relaxed and helpful, and kept apologising for the wait, but I still adopted that faux nonchalance I always put on when I am around the police. I have this notion, which I think is quite common, that I immediately look suspicious whenever I’m in their presence. So I try to appear calm, even bored. I don’t know what I am expecting them to do (suddenly shout, There he is! Seize him!)

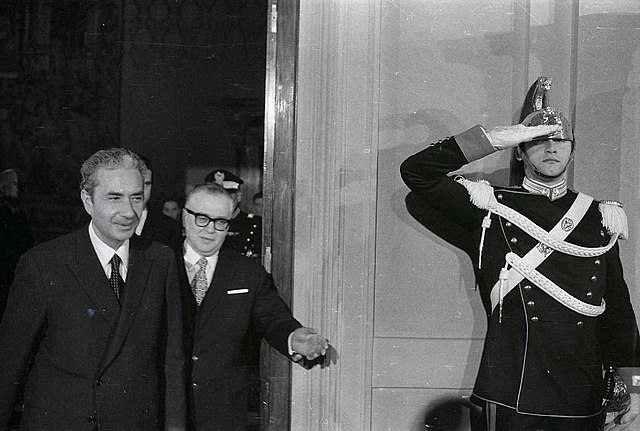

I thought about the public face of the law in Italy. Is there another country – apart from the United States – with such an array of forces? Carabinieri, Guardia di finanza, Polizia di stato. In Rome, the Polizia Locale di Roma Capitale (which is fun to say out loud). And, in the cities, troops from the Esercito Italiano protecting key sites. Each of these branches with their own distinct livery and vehicles and, presumably, responsibilities. I used to dwell on the reason for this profusion, and put it down to excessive fear mongering. But then on a visit to the Uffizi, I saw the imprint of a window scorched onto the ceiling, where a mafia bomb had exploded on the street outside in 1993. And later, in Rome, I stood beneath the giant plaque near the Capitoline where in 1978 Aldo Moro, the leader of the Christian Democrats and former prime minister, had been discovered in the boot of a Renault 4.

The police station was in the university quarter, near Bologna Metro. But I was staying for the month in Tor Vergata, beyond the city limits south-east of Rome. The nearest town was Frascati, renowned for its lovely wine, its beautiful villas and for being a sort of hub of the sciences. The German General Headquarters for the Mediterranean Zone were based in Frascati in 1943, and many monuments, homes and people were lost in bombing raids. The charming older core of the city has survived, perched atop a kind of acropolis. When reaching the summit, breathless, the effect is similar to that in Orvieto; a tight mediaeval maze surrounded by a brilliant vista of countryside (albeit Frascati is not as dreamily vertiginous as Orvieto, which is like something from a fairytale; one is in the clouds and the drop is sheer).

Tor Vergata, a few miles away, and containing only holiday or second homes, is less appealing. The railway and the motorway run through to and from Rome, and the only supermarkets were giant superstores which loomed on the periphery. It does share one notable feature with Frascati, though, which is that it is hilly. Infinitely, unimaginably, hilly. It is as if developers had asked a child to draw a series of comically undulating peaks and troughs, before saying ‘let’s find this, and build there’. When I left my apartment for the railway station, I climbed. And when I returned home of an evening, taking the same route, somehow I climbed again. The whole place was like an Escher staircase. I’d walk back, gasping and cursing, pursued at every step by a chorus of dogs snarling behind gated compounds.

The day before I was due to fly out to Italy, the owner of my accommodation in Tor Vergata got in touch. ‘Are you still arriving Saturday?’ ‘I am, yeah. That’s when I fly’. ‘Can you come on Sunday?’ ‘Er, not really. Like I said my flight is tomorrow’. ‘We’ve got a plumbing problem, and your room isn’t ready. The plumber will be out tomorrow. It’s not my fault’. He asked me to book elsewhere for the night. I ended up staying with Annalisa and her two-year old daughter (on my return home, Annalisa let me know that her car had subsequently been stolen). Miraculously, my room was ready by 9 the next morning, so the plumber must have arrived very early and completed the job, leaving no trace of ever having been there.

During my stay, the airwaves and the press were dominated by the death of Berlusconi. Talking heads went back and forth over looped stock footage and montage reels. The media was enjoying itself, but despite its obsession, Berlusconi’s death was more than a just media-driven event. Everywhere one went, his was the name on people’s lips. It wasn’t that they especially mourned or even celebrated his passing. It was more a recognition of an era having definitively ended. One man told me, in broken but impassioned English, that the former prime minister was a ‘mad dog’. Even the trendy bar I was sat in in Trastevere (a joint unlikely to be patronised by Berlusca supporters) switched over to the coverage of the funeral, though the owner did his best to undermine its solemnity by muttering obscenities throughout.

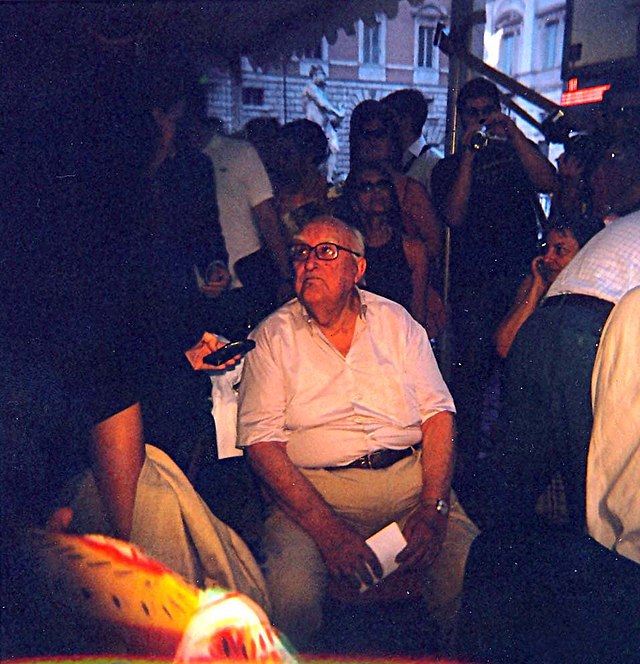

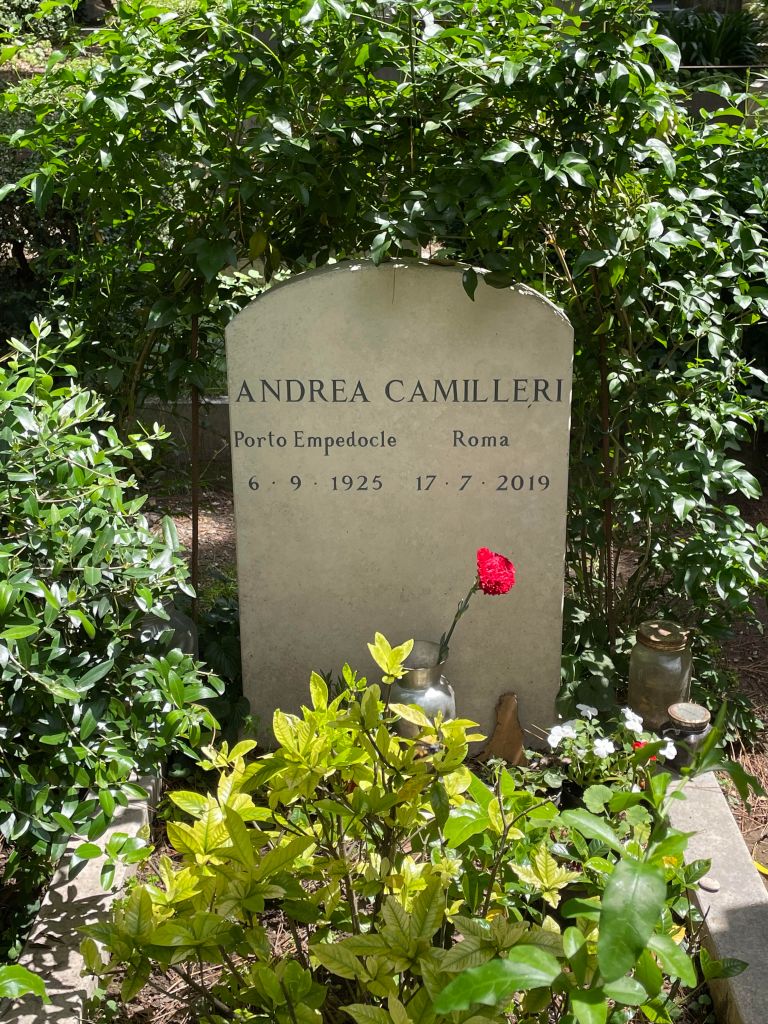

I was more interested in paying homage to an entirely different statesman of Italian life, one who represented a nobler vein. Andrea Camilleri, author of the Inspector Montalbano stories, while born in Sicily, had lived most of his life in Rome, where he died in 2019. He had been buried in the Protestant Cemetery near Porta San Paolo, adjacent to the Via Ostiense, the great trunk road to Ostia where St Paul had been martyred and entombed. I hadn’t been to this lovely place, my favourite cemetery, for years and so decided to return.

I have a small elegant Sellerio paperback of Camilleri’s Una voce di notte on my bookshelf which, with its liberal use of Sicilian, I have tried to struggle through only a handful of times. A few years ago, I was also given an English translation of La forma dell’acqua which was more gutsy and sweary than I’d expected. But I was and remain a big admirer of the TV adaptation of the novels. I grew up watching these on BBC Four, and I was so taken with them that I suppose I could claim that it was Camilleri’s creation that initiated my fascination with Italy. The plots and the characters of Camilleri’s Vigatan universe are both seductively exotic and utterly bizarre, though the more I visit Italy and the more Italians I meet, the less implausible I have found the show.

It felt appropriate that I should go and see him. So one midweek morning I took the Metro to Pyramide, crept out into the sunlight and shot between the traffic that swarms by the cemetery’s entrance. Known as the Non-Catholic, the English or the Protestant Cemetery, it is today host to people of every faith and none. For me, it is the most evocative place in Rome, partly bounded by the Aurelian Wall and by the shockingly white Pyramid of Cestius. Like a lot of special places, it doesn’t advertise itself much and is quite hard to find. Within, the graves jostle together on a gentle slope. It is populated by a colony of friendly cats, who sprawl on tombstones under the shelter of giant cypresses. Shelley, in a letter to Thomas Love Peacock, called it ‘the most beautiful and solemn cemetery I have ever beheld’.

Its romantic potency is intensified by the fame of those interred there, mainly artists and poets and writers, which is why Camilleri, along with his lack of religious faith, chose it as his place of repose. Shelley (sans heart) is buried there, and so is Keats, with a tombstone that doesn’t mention his name. But there is also Goethe’s son August and that bogeyman of the right, and co-founder of the Italian Communist Party, Antonio Gramsci. Keats’ and Shelley’s graves are impressive. But it is the graves of the less renowned that I find most moving. They either died abruptly far from home, or had settled in Italy and chose the cemetery as their last resting place. Their simple but beautiful tombs hint in their epitaphs of lives well lived. Far from inducing gloom, I always leave full of hope.

With a little help I found Camilleri near Gramsci, which I was told was a deliberate decision of Camilleri’s. His is a minimal, elegant grave with no account of his life or of his achievements.

I left invigorated. A short walk around the corner is another, newer cemetery, home to the Commonwealth dead of the Second World War, who had pushed their way up the peninsular in the face of Nazi opposition in 1943 and ’44. I went to pay my respects. Some 426 people souls are interred within, each with the distinctive headstone familiar to all Commonwealth burial sites. This cemetery, too, was demarcated by the Aurelian Wall, and, in a neat gesture of pleasing circularity, I saw displayed there a brick from Hadrian’s Wall, donated by the people of Carlisle to honour the fallen.

I later went to the Roman Forum and wandered around the Palatine, trying, and failing, to make sense of it all. I had paid extra for a super pass, which granted me access to a clutch of select sites. Two of these have stuck with me as impressive. The first is Santa Maria Antiqua, a fifth-century Byzantine church that was for a millennium buried under rubble and mud. It is only recently that it has been open to the public and boasts some incredible frescoes. Wholly Greek in character, it was used for worship when the Byzantine Empire was in its ascendancy. During this time, Rome’s population had dramatically shrunk. The city was nominally ruled by an exarch from Constantinople, who set up a base amid the fading ruins on the Palatine, but in reality it was administered by the increasingly powerful Bishop of Rome.

The other was the Curia Julia, the senate house. This rather bland and stolid looking building was the heart of Roman Imperial dominion, even as its powers were over the years diminished by the emperors. It was commissioned by Julius Caesar, who had enlarged senate membership to almost 1,000 people, but finished by Augustus. After Rome withered away, the building was for centuries used as a church. The opus sectile floor is said to be original. It did inspire some sort of awe, but as ever with such places, one needs to use imagination. I tried to picture a bored senator listening to a gabbing emperor. It’s not always easy. Theirs is a culture so remote. Whenever I stop to look at the Colosseum, or the Arch of Titus, I think not that ancient Rome forms part of the bedrock of Western civilisation, but how alien they and their civilisation seem.

I had spent a lot of time among the dead and the ghosts of the past, and felt I’d earned some rawer recreation. Towards the end of the month, I went with some friends to Stadio dei Marmi, part of the Foro Italico, a vast sports park (formerly Foro Mussolini; an obelisk with his name inscribed upon it still stands at the park’s entrance). The Marmi is an athletics stadium in the shade of the Olimpico, with a running track encircled by marble statues. It was an unusual event: 1,000 musicians playing together at once. It was magnificent, even just as a pure spectacle, and predictably deafening. There was something like 400 singers, 250 guitars, 250 drummers…. and so on. They covered Nirvana, Rage against the Machine, and, well, Coldplay, which I didn’t bother to pretend not to enjoy.

The concert was organised by Aperol. And they made sure you didn’t forget it. Not only were two glasses of Aperol Spritz on the house to every concertgoer, its warm orange signage and logo flashed and raced across every giant screen, and was plastered upon every square inch of free space. The compère told us that ‘we are all here tonight [pause] thanks to the generosity of Aperol! Everybody, give it up for Aperol!’ The crowd whooped. Perhaps ungratefully, I stayed silent. I instantly tried to imagine the same scene in Britain. ‘Put your hands in the air, one and all, for the proud sponsors of tonight’s event…Carling!’. Would a British crowd cheer? I thought they probably wouldn’t. I felt a very small swell of pride.

I have to confess something at this point. It’s uncomfortable, so it’s best to come right out with it. During the concert, I discovered that Italians can’t dance. Or at least, not in the way you are supposed to at a gig; not this crowd. I know this is rich coming from an Englishman. I truly do. Nevertheless, I can only report what I saw. In some ways, it is a compliment. After all, one doesn’t actually dance at a rock concert – it’s more jumping and bobbing and hands in the air. There is a skill to it though, and this crowd didn’t have it. Perhaps other Italian crowds do, at proper gigs not sponsored by Aperol. Italians, don’t worry: you know how to cook, how to eat, how to dress and how to live; you can’t have it all.